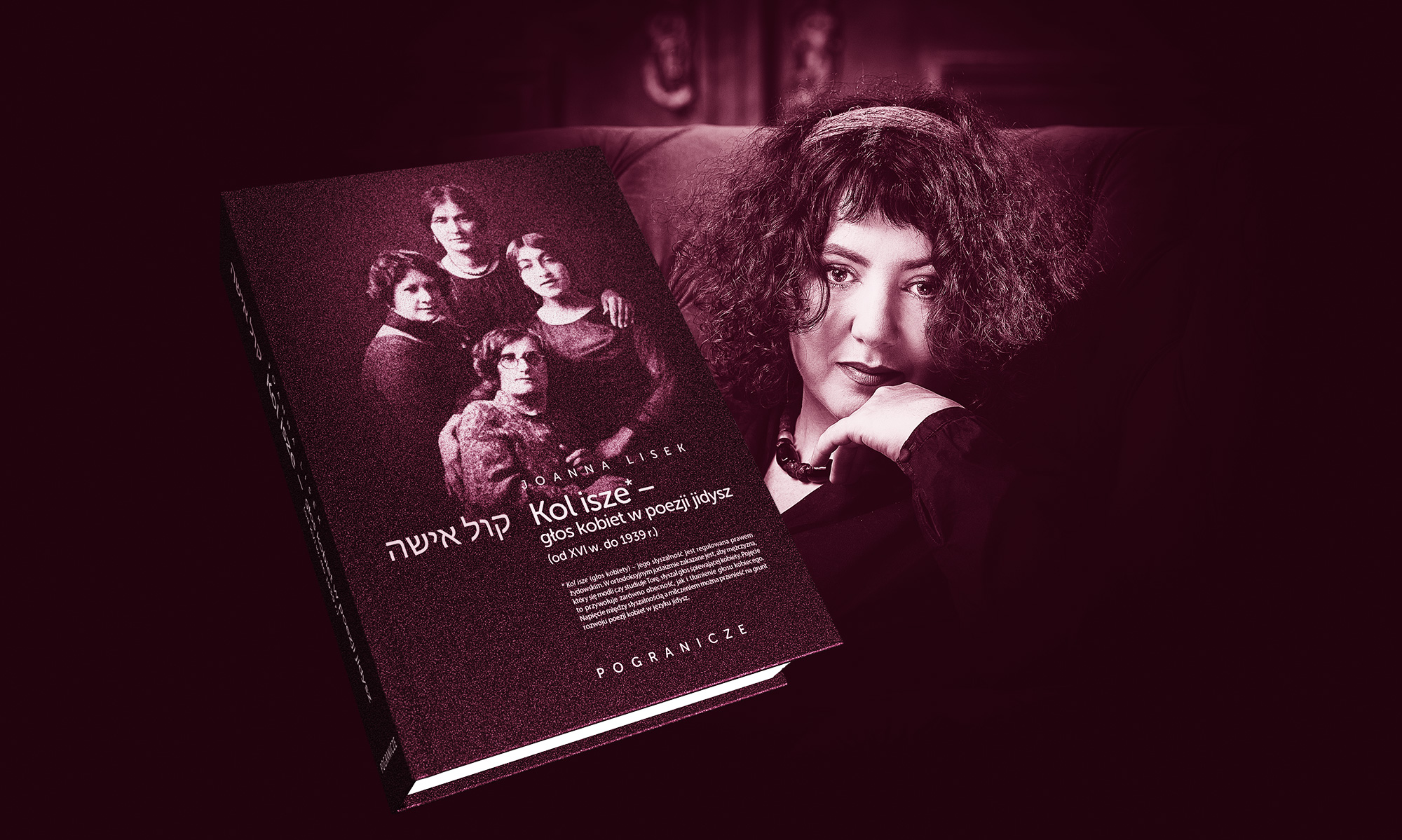

קול אישה

Kol ishe –

The Voice of Women in Yiddish Poetry from the Sixteenth Century to 1939

Over the course of five centuries, Yiddish poetry written by women created various models of femininity, developing along the way diverse strategies for expressing feminine subjectivity.

Writings by Jewish women in the Diaspora evolved under conditions that marginalized them in a three-fold manner: as representatives of a national and religious minority, as women functioning in a patriarchal system, and as artists writing in Yiddish, a language that, unlike Hebrew or Aramaic, was neither a source of prestige, nor a tool for power or for social promotion.

For centuries, writing has been one of the few available means for women to enter public spaces where their voices are audible. This reality is reflected in the title of the book, which refers to the concept of the kol ishe – the female voice. Its audibility was regulated by Jewish law as traditional Judaism prohibited a man from being within earshot of a singing woman due to the erotic effect attributed to her voice. Kol ishe implies both the presence and suppression of the female voice. This tension between audibility and silence can be regarded as the perfect metaphor for the development of women’s poetry in Yiddish.

Kol ishe – The Voice of Women in Yiddish Poetry from the Sixteenth Century to 1939 commences with the earliest texts of the 16th century, when women poets were preachers, authors of prayers and religious songs, or typesetters who recorded their texts on the margins; then proceeds to an examination of folk art, which often expressed criticism of the established gender order; and concludes with works that testified to the moral revolution of the twentieth century with its accompanying radicalization of attitudes and transformation of the model of Jewish femininity. The subject of this study is to investigate both how women functioned within their limits and how they pushed those limits; how they broadened the scope of their activities; and how they redefined their role and position so as to leave their own unique mark.

The history of Yiddish poetry created by women is treated here diachronically, with the historical and literary discussion being closely connected to the examination of specific cases of creative authorship and the interpretation of selected poems. Included are well-known poets together with authors who are less recognizable, overlooked or simply forgotten.

The introduction discusses the relationship between femininity and Yiddish. The first part presents the position of women in Yiddish literature as it developed from the thirteenth to the eighteenth century: beginning with the reader and patron, and then expanding to include the authors that began to appear in the sixteenth century, who were, above all, women poets.

In works that were primarily of a religious character, these poets wrote first and foremost as faithful adherents of Judaism upholding their moral purity (also understood as corporal purity); devoted daughters of Israel banished, persecuted, and awaiting redemption. On occasion, they even recorded their personal voice in the margins of books that they bound by hand in printing shops (as did, for example, Ele and Gele, the daughters of Moishee ben Avrom Ovinu).

Although their texts did not criticise patriarchal gender divisions, they clearly encouraged women to be active, while the poets themselves wrote sermons (Khana Katz), and arranged songs for Simkhes Toyre (Ryvke Tiktiner) or songs commemorating important historical events (Toybe Pan) that broadened the limits of erstwhile social role models.

This section also analyses female subjectivity in Jewish folk songs popular in the 19th century (many of which were most probably written earlier). The lyrics often contained criticism of the established gender order, of arranged marriages, of the difficulties of being a wife and mother. There are references to young girls sexually abused before marriage and then abandoned, and even faint complaints of physical violence in the home. One of the more fascinating aspects of both the women’s texts in old Yiddish literature and in folk mikvah songs is the fact that they clearly take into account and articulate the issue of corporeality, which obviously ties into the important role of the ritual purity of the female body in Judaism.

The second part examines the contribution of women poets to modern Yiddish literature. The fundamental changes that took place in Yiddish literature at the beginning of the nineteenth century had at their roots the expansion of two developments in Jewish culture: the Haskalah and Hasidism. Both these movements were deeply androcentric in nature and did not allow for any space in which women could hope to be creatively active until the 1880s, when a new period of Yiddish poetry emerged. This section of the monograph is divided into two periods: the first spans from 1888 to 1918, when the various forms of female expression were established, from imitation and camouflage to the first attempts at speaking clearly in their own voice. The second period covers the years 1918 to 1939, by which time women’s poetry had become a clearly recognizable, distinct, and debated component of Yiddish literature. It was during this period that the most distinguished artists came into their own, including Kadya Molodowsky, Celia Dropkin, and Debora Vogel; it was at this point that Ezra Korman edited Yiddishe dikhterins, a collection of the works of seventy women poets and one of the most important literary anthologies ever published in Yiddish.

The flourishing of the creativity of women poets is situated along geographical lines and aligned with the largest centers of Yiddish culture: in Poland (Lodz, Warsaw and Galicia), in the United States (New York), and in the Soviet Union (Moscow), including two major centers of Yiddish in Ukraine, Kiev and Kharkiv.

The changes introduced by women into Yiddish literature during this second period were primarily of a thematic nature: in the creation of a distinct lyrical “I,” in the manner in which women’s experiences were recorded, in the expansion of the boundaries of intimacy. In their work, the women poets sought to rebel against traditional forms of female existence; they expressed a desire for independence and social recognition. The poetry of the women of this period speaks to a revolution of manners, the radicalization of attitudes, and transformations that refashioned the traditional model of Jewish femininity. The women poets began scrutinizing motherhood, corporality, eroticism, and creativity from a completely new perspective.

Within this new definition of femininity, we can, generally speaking, distinguish three models of women: as emancipated, as religious feminists, and as revolutionaries.

The first model was formed by progressive feminist circles, and was the model of a liberated woman living in the spirit of modernity, departing from the values of her female predecessors while still bearing the imprint of her mothers and grandmothers (e.g., the poems of Rashel Veprinsky, Celia Dropkin, Kadya Molodowsky).

The second model, popularized in the feminizing circles of Jewish neo-Orthodoxy, was the ideal of the so-called “New Rachel:” a young woman who consciously chose a religious identity, upholding the women’s traditions developed in Yiddishkeit (Jewishness); a woman who wanted to remain a proud guardian of Jewishness, but at the same time clearly emphasized her subjectivity and was educated, active, and oriented in political and social problems (e.g., the poetry of Roze Yakubovitsh or Miriam Ulinover).

The third model was closely related to post-revolutionary changes in the USSR and the image of the New Socialist Woman: equal with her male peers, an active participant in productivization, fighting on the front with a rifle on her shoulder, and struggling to define a new type of relationship between the sexes based on free love (the works of Aniuta Piatygorska and Khane Levin).

Radical women’s voices in Yiddish poetry repeatedly met with disapproval in literary criticism. Secular critics of Yiddish, often authors of modern, avant-garde literature that openly rejected Jewish traditional values, expected conservatism in works by women. They wanted women to champion a variety of Jewishness that guaranteed the continuity of their mothers’ and grandmothers’ customs.

This book reveals the presence of female poetic expression in oral traditions and in the printed word, and describes how men consistently sought to regulate forms of female creativity, primarily through publishing institutions and literary criticism. By analysing common and recurring themes, motifs and thematic subjects, this study records the female experience over the span of several centuries through the prism of poetry written by women.

Translation by Barbara Pendzich